Sensory Washi

2019 | Handmade Conductive Paper

The ongoing project Sensory Washi envisions new technological aesthetics based on traditional crafts and local knowledge. In the prefecture of Shimane, the art of handmade Sekishu Washi has been maintained and passed on within family run workshops for more than 1.500 years. Sekishu Washi made from locally grown kozo (mulberry bark) is well known as the strongest paper produced in Japan.

How to deal with such craft heritage today – conserve or update? In 2019 Jonas Althaus worked in close collaboration with local artisans on an exciting addition to the original recipe: Enriched with conductive supplements the sheets turn into sensors receptive to touch, proximity and air-humidity.

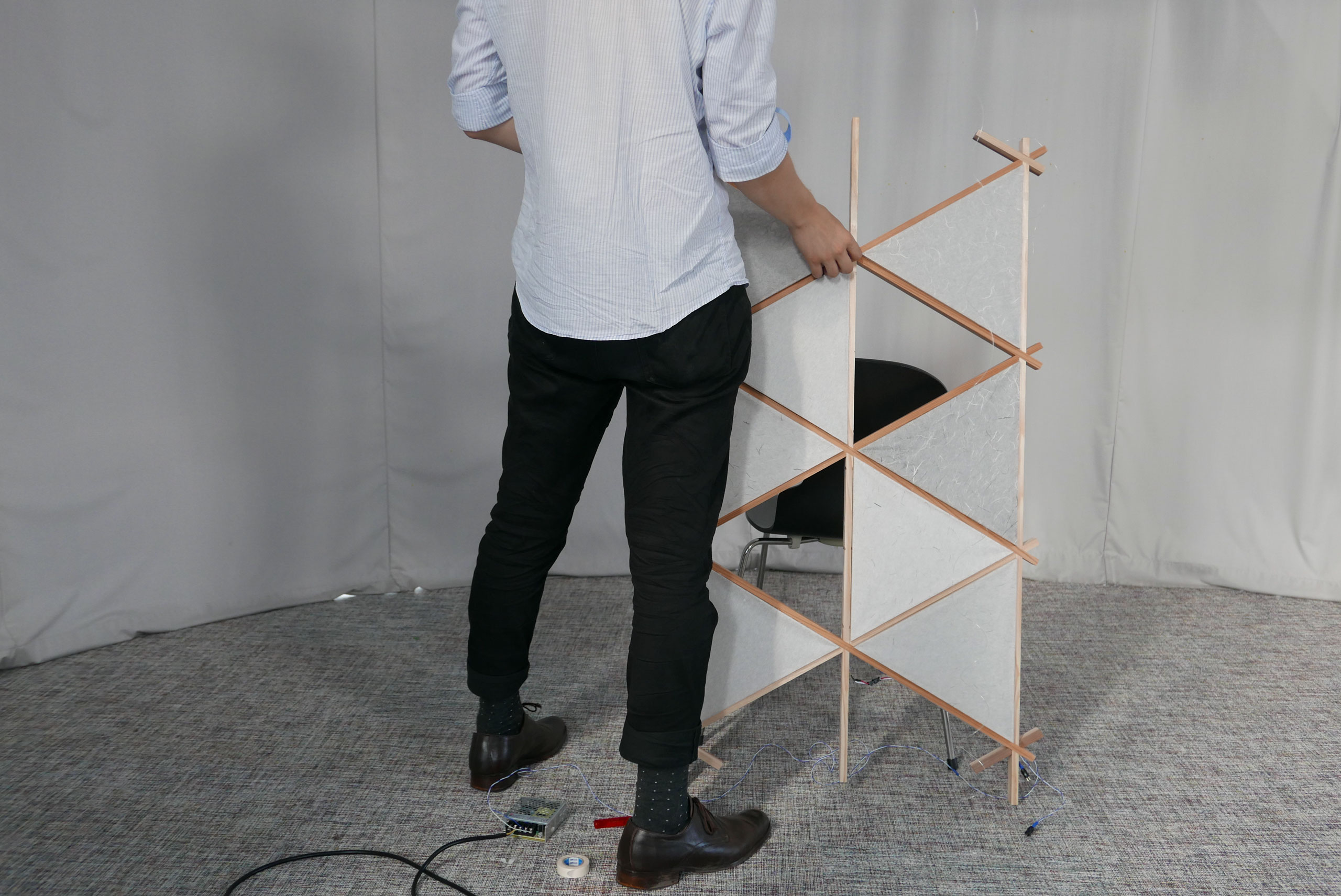

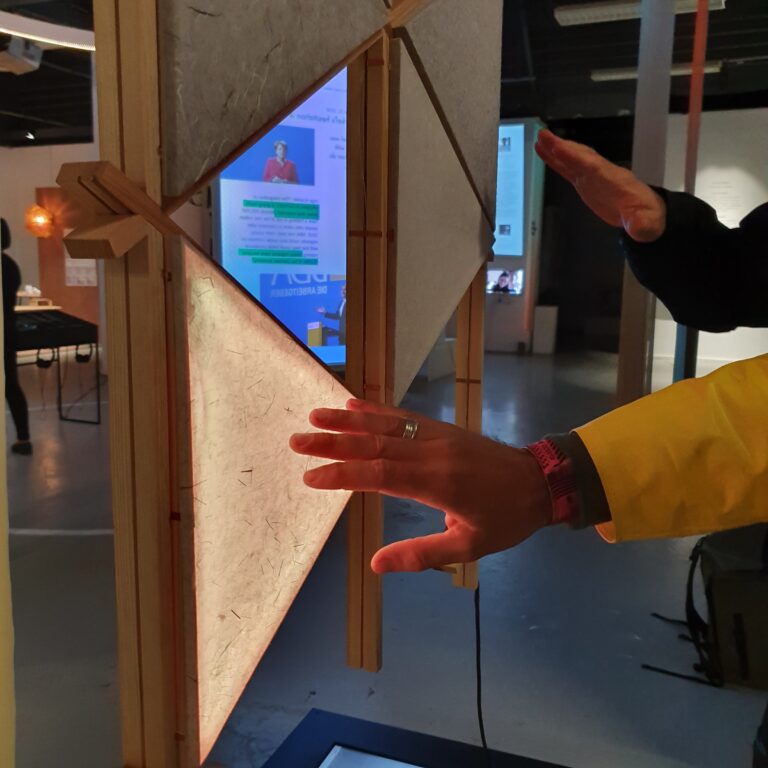

The design of a preliminary prototype is a touch-interactive glowing room divider, integrating the developed washi material and Japanese woodcraft technique. This spatial element once again draws on the interplay of washi and light – and it makes the potential of washi experienceable in a new way.

This project was supported by MONO Japan AIR program. In collaboration with Sekishu Washi Center Misumi Hamda, sekishu washi workshops Kubota and Nishida

Sensory Washi paper connects old tradition to futuristic applications. In Japanese architecture, handmade paper was once widely used (to build paper walls shoji, famous for their interplay with natural light), but lost its popularity in modern homes.

In 1933, the Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki pondered over the painful loss of traditional aesthetics, of century-old living concepts which were replaced because technological progress seemingly called for modernist (=Western) shapes, materials and design paradigms (In Praise of Shadows, Tanizaki 1933).

It would be interesting to hear Tanizaki’s evaluation of “high-tech” living environments today: Seemingly smart or connected homes which perform an impressive amount of digital tasks – yet fail to enrich their inhabitants on a sensual level close to that of bygone times:

“No words can describe that sensation as one sits in the dim light, basking in the faint glow reflected from the shoji, lost in meditation or gazing out at the garden”.

Regarding contemporary architecture and interior design with Tanizaki’s eyes, it becomes clear that the profound knowledge in craftsmanship about the interplay of light, textures and colors once present in Japanese interiors deserves a revaluation.

Can these seemingly outdated production processes bring back material richness, sensuality and hand crafted products to our future homes?